Open Science

Methoden der empirischen Kommunikations- und Medienforschung

Freie Universität Berlin

Fragen zur Übung?

Falls nicht: Besprechung von Aufgabe 2

Open Science

Mit Material von Prof. Tobias Dienlin, Universität Zürich. Original hier

Agenda

- Warum Open Science?

- Open Science: Definition und Praktiken

- Kritik an Open Science (Praktiken)

Warum Open Science?

Warum Open Science?

OS als Reaktion auf Probleme

OS als Umsetzung wissenschaftlicher Prinzipien

OS als Reaktion auf Probleme

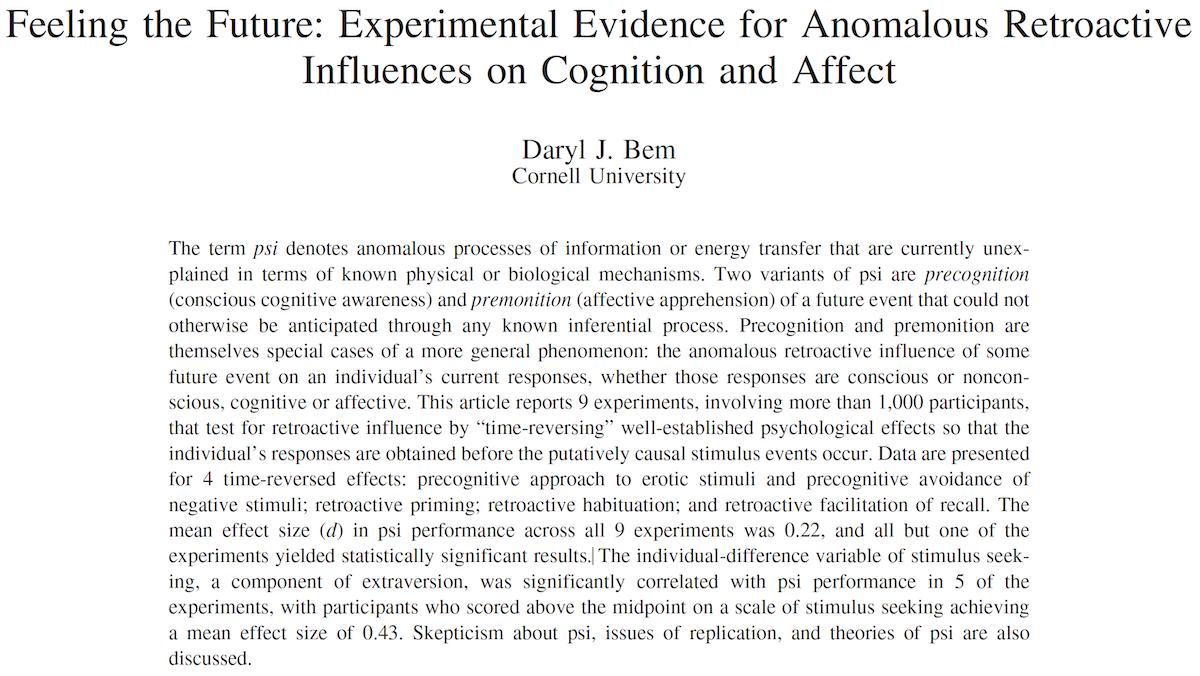

Feeling the Future

Design

- 9 unabhängige Experimentalstudien

- Mehr als 1,000 Versuchspersonen

Beispiel: Precognitive Detection of Erotic Stimuli

- Zwei virtuelle Vorhänge

- Raten: Hinter welchem Vorhang ist ein Bild?

- Position des Stimulus wird erst nach Raten durch Zufallsgenerator festgelegt.

- Vergleichsgruppen: Erotische und nicht-erotische Bilder

Feeling the Future

Your task is to click on the curtain that you feel has the picture behind it. The curtain will then open, permitting you to see if you selected the correct curtain.

Feeling the Future

Versuchsperson rät.

Zufallsgenerator legt Position des Bilds fest.

Ausgewählter Vorhang wird geöffnet.

Feeling the Future

“Across all 100 sessions, participants correctly identified the future position of the erotic pictures significantly more frequently than the 50% hit rate expected by chance: \(53.1\%\), \(t(99) = 2.51\), \(p = .01\), \(d = 0.25\).”

Feeling the Future

“In contrast, their hit rate on the nonerotic pictures did not differ significantly from chance: \(49.8\%\), \(t(99) = 0.15\), \(p=.56\). This was true across all types of nonerotic pictures: neutral pictures, \(49.6\%\); negative pictures, \(51.3\%\); positive pictures, \(49.4\%\); and romantic but nonerotic pictures, \(50.2\%\). (All \(t\) values \(<1\).) The difference between erotic and nonerotic trials was itself significant, \(t_{\text{diff}}(99) = 1.85\), \(p = .031\), \(d = 0.19\).”

Feeling the Future: Diskurs

- Ergebnisse stellen etablierte Naturgesetze infrage.

- Offiziell in einer der wichtigsten Fachzeitschriften für Psychologie publiziert; entspricht den methodischen Standards des Felds und der Zeit

Implikationen

- Precognition existiert (und wir können die Ergebnisse replizieren)

- Precognition existiert nicht (und die methodischen Standards sind ungenügend)

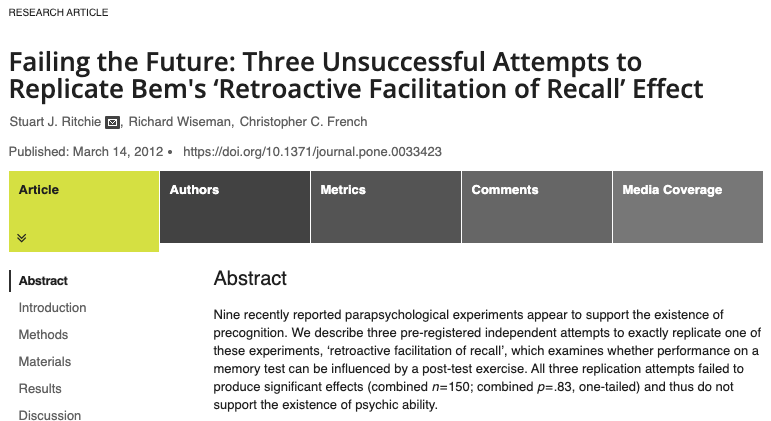

Feeling the Future: Diskurs

- Gleiches Design, gleiche Analyse

- “All three replication attempts failed to produce significant effects (combined n = 150; combined p = .83, one-tailed) and thus do not support the existence of psychic ability.”

- Von der Fachzeitschrift ohne Review abgelehnt: Keine Publikation von Replikationsstudien

Feeling the Future: Diskurs

Daryl Bem

“I’m all for rigor,” he continued, “but I prefer other people do it. I see its importance—it’s fun for some people—but I don’t have the patience for it.” It’s been hard for him, he said, to move into a field where the data count for so much. “If you looked at all my past experiments, they were always rhetorical devices. I gathered data to show how my point would be made. I used data as a point of persuasion, and I never really worried about, ‘Will this replicate or will this not?’”

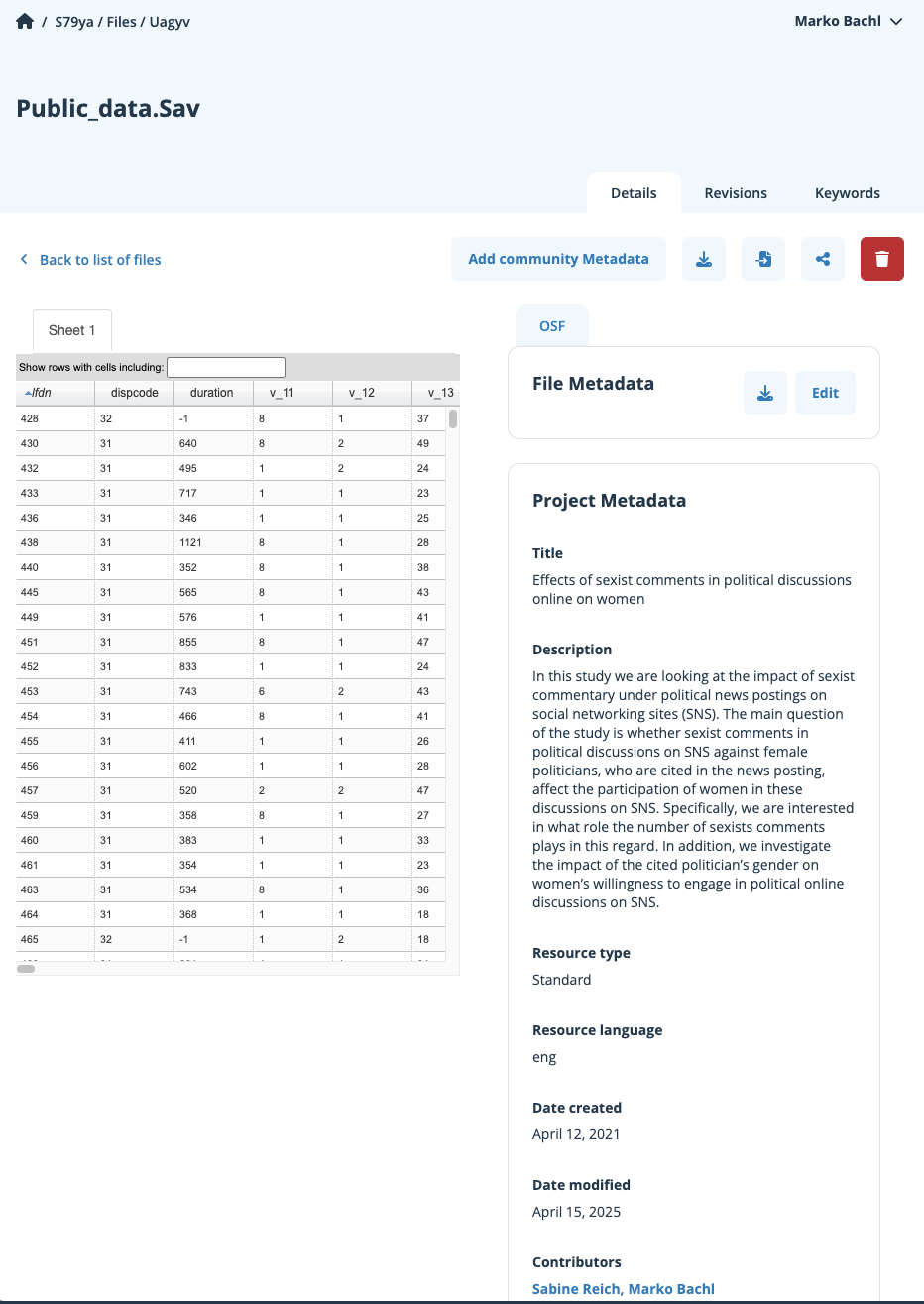

Open Science Collaboration (2015)

- Replikation von 100 “wichtigen” Studien aus der Psychologie

- 39% “erfolgreiche” Replikationen

- Durchschnittliche Effektstärke:

- Replikationsstudien: \(M_r = .2\)

- Originalstudien: \(M_r = .4\)

Verbreitete Erklärungen

- Betrug

- Fragwürdige Forschungspraktiken (Questionable Research Practices [QRPs])

- Fehler

- Publikationsbias

Verbreitete Erklärungen

- Betrug

- Fragwürdige Forschungspraktiken (Questionable Research Practices [QRPs])

- Fehler

- Publikationsbias

Betrug

Prominenter Fall in der Psychologie: Diederik Stapel

- Ehemaliger Professor für Sozialpsychologie an der Universität Tilburg

- Erfolgreich, sehr produktiv

- 2011: Entlassung wegen der Fälschung von Datensätzen, Erfinden von Studien

- Bisher 58 Retractions (zurückgezogene Artikel) laut Retraction Watch Leaderboard

- Aufschlussreiche Autobiographie (Stapel, 2014)

Aktueller: Francesca Gino (Harvard Business School): Data Colada

Betrug

“I preferred to do it at home, late in the evening, in fact at the beginning of the night, when everybody else was asleep. I would make some tea, put my laptop on the kitchen table, get my notebook from my rucksack, take my fountain pen out, and make a careful list of all the results and effects I needed to create for the study I was doing. Neat tables with the results I expected based on extensive reading, theorizing, and thinking. Simple, elegant, comprehensible. Next I started to enter the data, column by column, row by row. I tried to imagine how the participants’ answers to my questionnaire would look. What were some reasonable answers that might be expected? 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 4, 5, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 5, 4, 3, 3, 2. When I’d input all the data, I ran some quick preliminary analyses. Often these didn’t show what I was expecting, so I went back to the matrix of data to change a few things. 4, 6, 7, 5, 4, 7, 8, 2, 4, 4, 6, 5, 6, 7, 8, 5, 4. And so on, until the analyses came up with the results I was looking for. That is, until the data showed what was logical, and therefore true.”

Verbreitete Erklärungen

- Betrug

- Fragwürdige Forschungspraktiken (Questionable Research Practices [QRPs])

- Fehler

- Publikationsbias

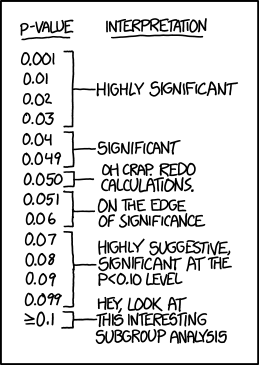

QRP 1: P-Hacking

Datenanalyse mit dem Ziel “statististischer Signifikanz” (p < .05)

Viele Variablen erheben

Viele Varianten der Datenaufbereitung testen

Viele Analysen durchführen

Fälle aus Analyse ausschließen

Weitere Fälle erheben

Während der Studie auswerten und abhängig von Zwischenergebnis stoppen

Am Ende: Selektiv berichten, was “funktioniert” hat

QRP 2: HARKing

- Hypothesen nach Datenanalyse formulieren (Hypothesizing After Results are Known)

- Erlaubt das Erzählen schlüssiger, widerspruchsfreier “Geschichten”

- Eigentlich offensichtliche Umkehr der Logik des deduktiven Testens von Hypothesen und Theorien

- “Es ist kein HARKing, wenn man die Hypothese davor hätte haben können” (prominenter Kommunikationswissenschaftler, pers. Kom.)

- Es ist einfach, sich selbst einzureden, man hätte die Hypothese eigentlich schon immer so gehabt.

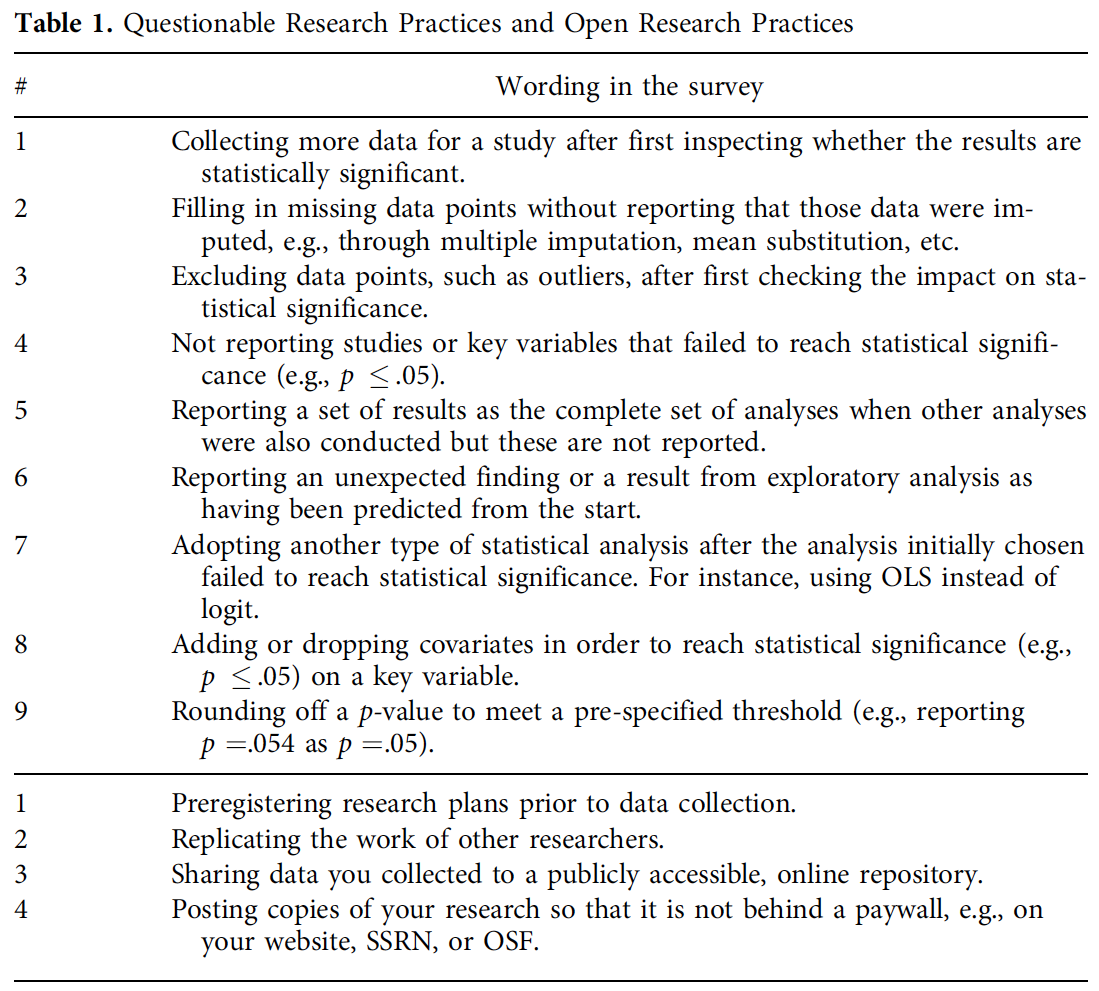

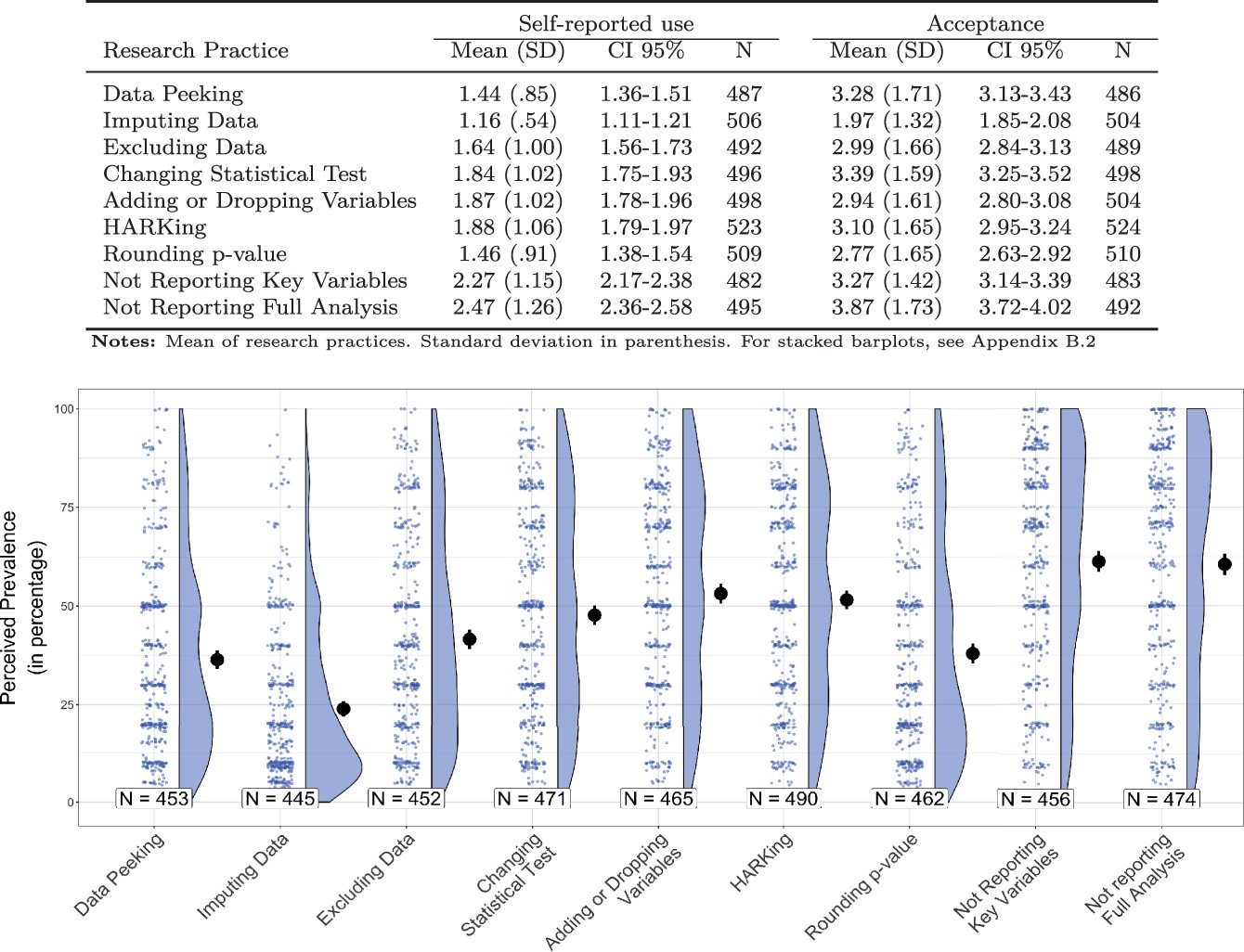

QRPs: Verbreitung in KW

QRPs: Verbreitung in KW

Verbreitete Erklärungen

- Betrug

- Fragwürdige Forschungspraktiken (Questionable Research Practices [QRPs])

- Fehler

- Publikationsbias

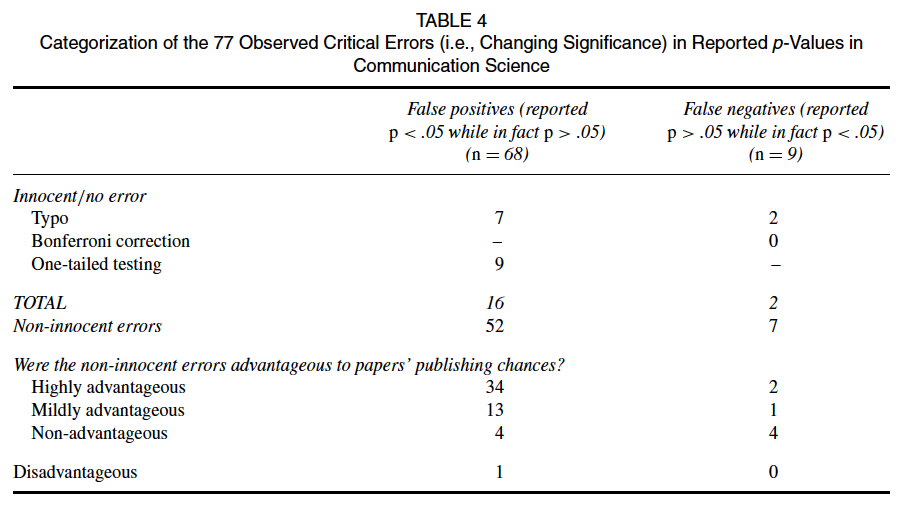

Fehler

- Technische Fehler bei Datenmanagement oder Analyse (z.B. Codieren einer Variable)

- Fehler beim Berichten von Ergebnissen (Beispiel: falsche p-Werte)

- Einerseits: Irren ist menschlich.

- Andererseits: “hilfreiche” Fehler häufiger

- Unschuldige Erklärung: Wenn Ergebnis nicht “stimmt”, wird genauer geprüft

Verbreitete Erklärungen

- Betrug

- Fragwürdige Forschungspraktiken (Questionable Research Practices [QRPs])

- Fehler

- Publikationsbias

Publikationsbias

Entscheidung der Herausgeber:innen von Fachzeitschriften: Studien mit “statistisch signifikanten” Ergebnissen haben bessere Publikationschancen

Entscheidung der Wissenschaftler:innen: Studien mit nicht “statistisch signifikanten” Ergebnissen verschwinden in der Schublade (file drawer)

Betrifft unter anderem nicht erfolgreiche Replikationsstudien

Folge: Verzerrter Forschungsstand, selbst wenn die publizierten Studien unverzerrt sind

Warum Open Science?

OS als Reaktion auf Probleme

OS als Umsetzung wissenschaftlicher Prinzipien

Nachvollziehbarkeit als wissenschaftliches Grundprinzip

- Royal Society (1662): “Nullius in verba” (take nobody’s word for it)

- Abgrenzung von der Autorität von Institutionen (Kirche) oder Personen (König)

- Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse müssen überprüfbar sein

- Voraussetzung: Transparenz und Veröffentlichung eines möglichst großen Teils des Forschungsprozesses

Fragen?

Open Science: Definition und Praktiken

Weite Definition

Definition für empirische Studien

Open science refers to the process of making the content and process of producing evidence and claims transparent and accessible to others. Transparency is a scientific ideal, and adding ‘open’ should therefore be redundant (Munafò et al., 2017, S. 5).

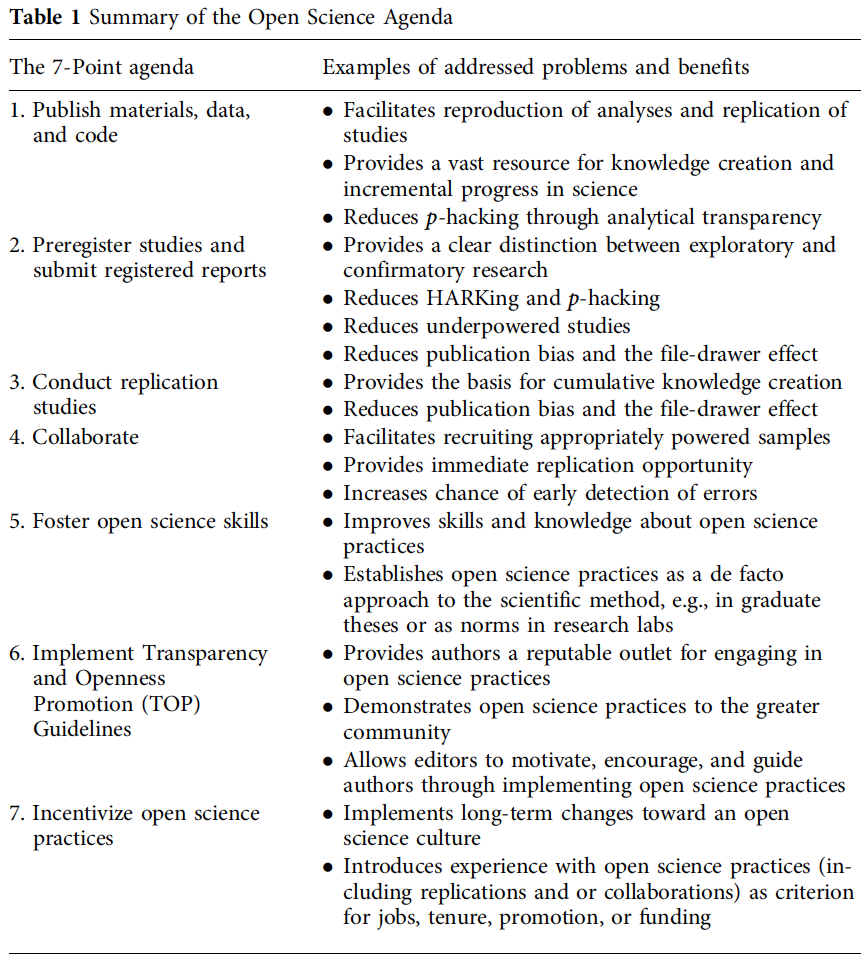

Agenda for Open Science in Communication

Open Science Praktiken

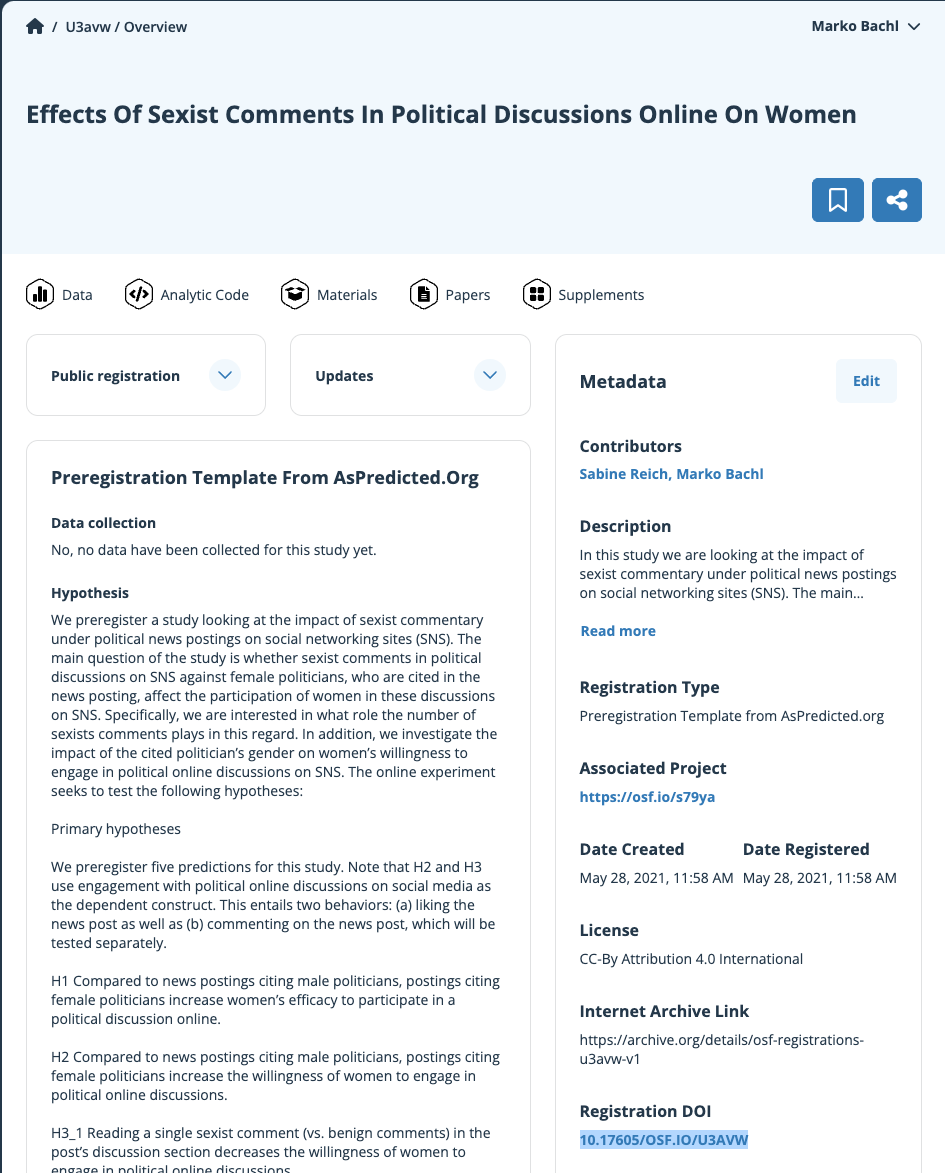

Präregistrierung

- Veröffentlichung von Hypothesen und Studiendesign vor der Datenerhebung

- So konkret wie möglich

- Gut: Öffentlich verfügbare Präregistrierung; anonymisiert im Begutachtungsverfahren einbringen.

- Besser: Registered Report (Einreichen der Präregistrierung, Verbesserung durch Begutachtungsverfahren, konditionale Annahme zur Veröffentlichung vor Studiendurchführung)

- https://aspredicted.org/: Einfache Präregistrierung

- https://osf.io/registries/: Viele Vorlagen

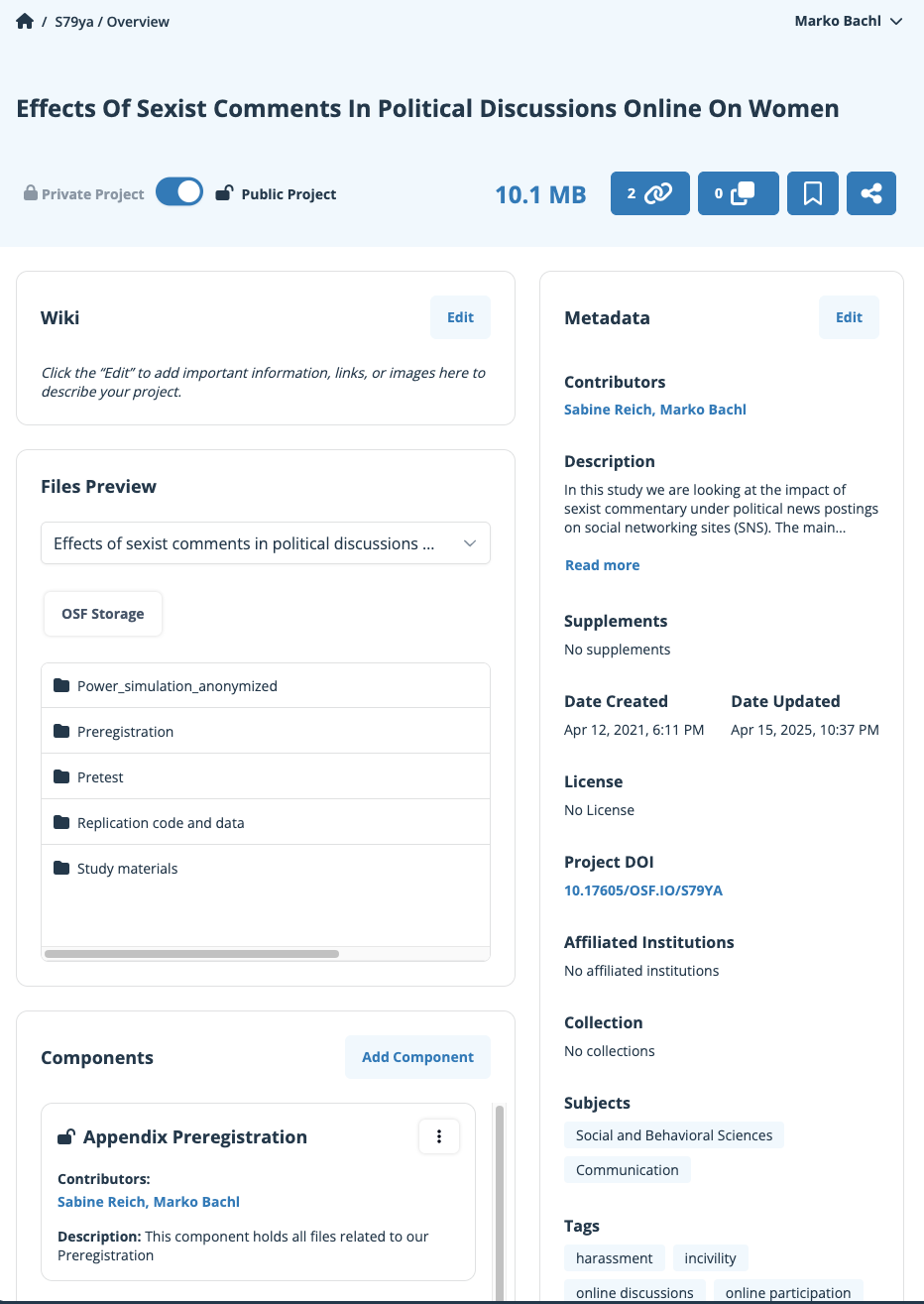

Veröffentlichung von Daten

- Möglichst von Rohdaten bis zu Analysedaten

- Einige Daten können aus guten Gründen nicht veröffentlicht werden.

- “Among articles stating that data was available upon request, only 17% shared data upon request” (Hussey, 2025)

- https://osf.io/: Einfach, aber unübersichtlich

- https://dataverse.org/: Etabliert in Politikwissenschaft

- https://zenodo.org/: EU-Projekt

- https://www.gesis.org/datenservices/daten-teilen: Professionelle Archivierung sozialwissenschaftlicher Datensätze

Veröffentlichung von Material

- Alles denkbare, teilbare Material, um Studie nachvollziehbar zu machen

- Planung: Vorstudien, Power-Analyse, Design

- Durchführung: Instrumente, Stimuli, Versuchspläne, Stichprobenpläne

- (Daten in verschiedenen Schritten des Forschungsprozesses)

- Analyse: Skripte zu Datenaufbereitung und Analyse

Kritik an Open Science (Praktiken)

Kritik an Open Science (Praktiken)

- Open Science alleine garantiert keine qualitativ hochwertige Forschung

- Nicht evidenzbasiert und nicht an Kommunikationswissenschaft angepasst (Freiling et al., 2021)

- Open Science (wie im Mainstream praktiziert) verstärkt Marginalisierung von Themen, Populationen, Forschenden (Fox et al., 2021)

- Open Science (wie im Mainstream praktiziert) folgt einer westlichen, kapitalistischen Logik (Dutta et al., 2021)

- Mehr lesen: Special Issue des Journal of Communication (Shaw et al., 2021)

Fragen?

Nächste Einheit

Agent-based simulation (Prof. Annie Waldherr, Uni Wien)

Danke — bis zur nächsten Sitzung.

Marko Bachl