|

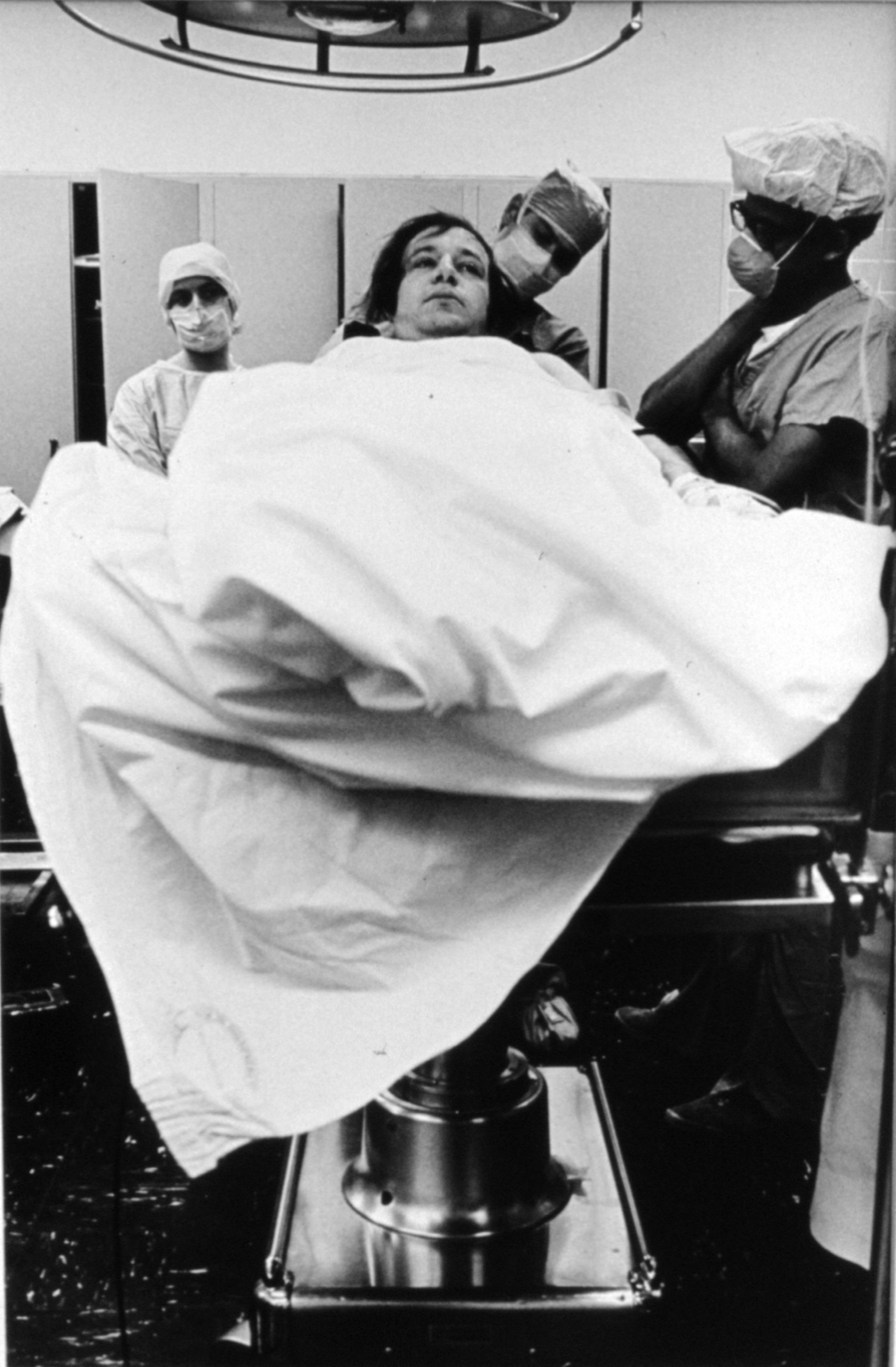

Aram Yardumian (Philadelphia) The Death of the Hero-Surgeon: Mitchell Payne's The Patient as ObjectMitchell Payne's The Patient as Object commands our attention both as a work of art and a view of the history of medicine. It is an apologia to physicians of sterling character, and a belief in the value of human contact in medical practice. It is also a vision of life transformed and suspended, and of the void where the hero-physicians once stood. Payne's camera roves the sterile tile-grid walls of the subterranean chambers, recording the occasional spark of light on a grim horizon. Jumbled, emptied of color, and bereft of all self-consciousness, the patients can do nothing to conceal their ignominy from the camera, while automatous caregivers pace blithely around the room, impervious to the electricity emitted by humans at their mortal and psychic limits. Why must the noble act of preservation of life hatch the aesthetics of nightmare? Why must the advancement and speed of technology dehumanize both the patient and the caregiver at, seemingly, inverse ratios? Must technology cool the relationship between physician and patient? These are some of the questions asked by the author of The Patient as Object as a witness to the formative years of mechanical and electronic machines in American surgical procedure. Mitchell Payne's The Patient as Object commands our attention both as a work of art and a view of the history of medicine. It is an apologia to physicians of sterling character, and a belief in the value of human contact in medical practice. It is also a vision of life transformed and suspended, and of the void where the hero-physicians once stood. In thirteen1 cold, sometimes abstruse images, mute bodies reflect their disorientation back at us, through anesthetic haze, with a vulgarity approaching that of Grunewald's Christ. The author of the photographs, Mitchell Payne, an American, stands invisible, as if from beyond the walls of the operating chamber, yet he casts intense empathy into the images, writing their subjects large yet depleted, and in a smaller way hopeful. Payne's camera roves the sterile tile-grid walls of the subterranean chambers, recording the occasional spark of light on a grim horizon. Jumbled, emptied of color, and bereft of all self-consciousness, the patients can do nothing to conceal their ignominy from the camera, while automatous caregivers pace blithely around the room, impervious to the electricity emitted by humans at their mortal and psychic limits. Why must the noble act of preservation of life hatch the aesthetics of nightmare? Why must the advancement and speed of technology dehumanize both the patient and the caregiver at, seemingly, inverse ratios? Must technology cool the relationship between physician and patient? These are some of the questions asked by the author of The Patient as Object as a witness to the formative years of mechanical and electronic machines in American surgical procedure. PhiN 52/2010: 51

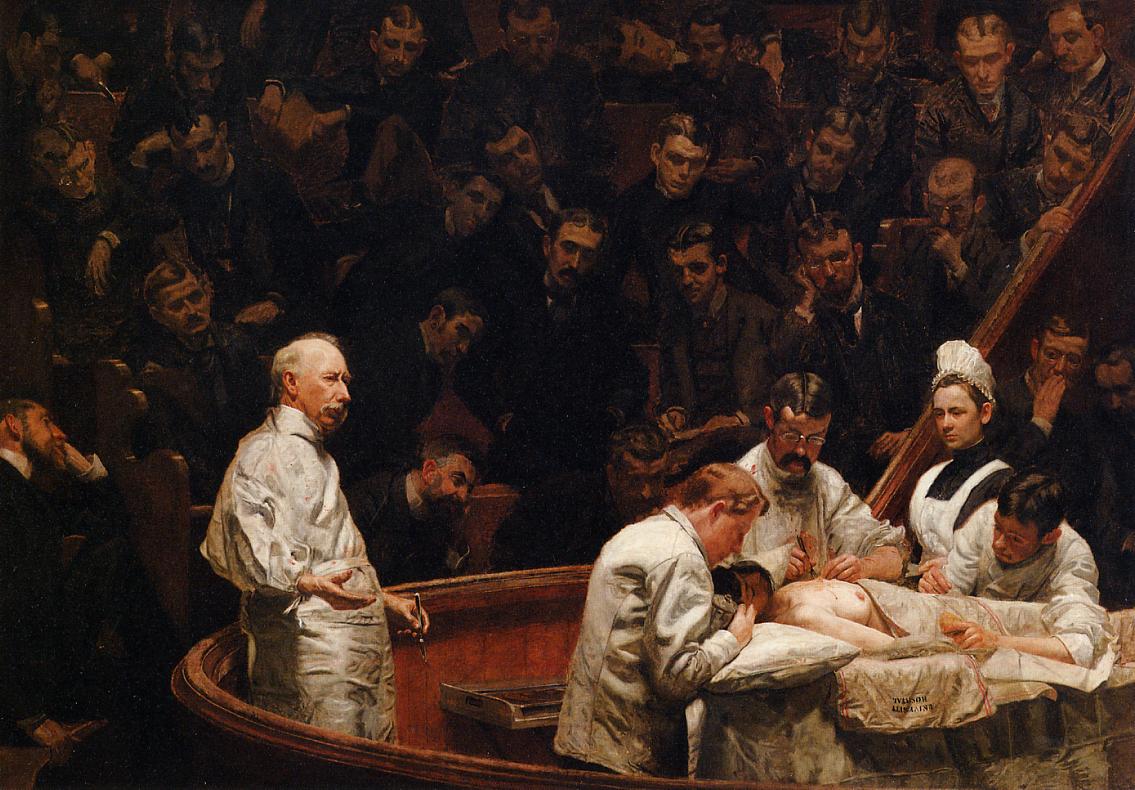

PhiN 52/2010: 52 The series, in this sense, invites comparison to two famous paintings by Thomas Eakins, The Gross Clinic (1875, Figure 1) and The Agnew Clinic (1889, Figure 3), which dramatically depict two famous Philadelphia surgeons at a time in history when their heroic roles in the medical world were approaching the crest of profound change. Mitchell Payne was also moved by the iconic hero-surgeon and the advances of medicine in his lifetime but, unlike Eakins, found only the vestiges of these values in what was once again an operating room undergoing a shift in technology.

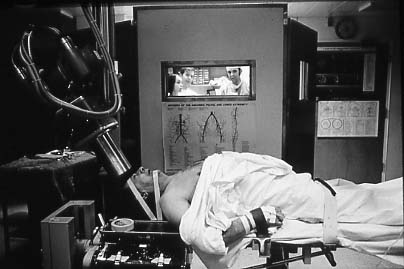

PhiN 52/2010: 53 What ultimately became The Patient as Object began in late 1970 as Mitchell Payne's Masters of Fine Arts thesis at the Rochester Institute of Technology. The project went through two distinct stages of development, first as a search for what Payne called "the magical, superhuman qualities of a hospital and its staff" and the "human frailty of the staff and its patients" (Payne c1970); and second, his disillusionment. His initial compulsion to dispel the very disillusionment he later succumbed to was theoretically, if not aesthetically, akin to Eakins, who once declared in an exasperated defense of The Agnew Clinic: "All I was trying to do was picture the soul of a great surgeon" (Kirkpatrick 2006: 398). Payne and Eakins both saw the surgeon as a great man of society and worthy of immortalization, but Payne also greatly admired his brother Nettleton Payne, a neurosurgeon-in-residency at the time. Although today we are quite used to medical drama in print and on television, in the early 1970s it was uncommon for a journalist or art student to be granted an insider's perspective of the hospital. Payne managed to secure unrestricted access, presumably with help from his brother, to the operating rooms of Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester, New York; however, individual staff members had difficulty believing it. This prompted Payne to stay close to one surgeon, a neurosurgeon-in-residency whom he refers to as "Dr. Duke"2 , whose professional life Payne set about documenting. His vision at this time was an empathetic study of "the hard, challenging life of a doctor" (Payne c1970-72) which he hoped to translate into series of portraits and action shots. Payne's work also met critical obstacles that in turn led him to see the operating chamber more objectively. After two months with "Dr. Duke" Payne presented his work, Neurosurgeons in Action, to members of his graduate committee, but the response was overwhelmingly negative. They berated it as "trite" and "cliché" and said it "presented a sympathetic view of medicine which they had seen time and time again". The entire project, they claimed, "rang of sentimentality" (Payne c1970-72). During his reconnaissance of Strong Memorial Hospital, Payne noted what he described as "many sophisticated machines, instruments and analyzers that seemed as if they belonged in 2001: A Space Odyssey" (Payne c1970).3 A fascination with these machines not evident in the earliest work had grown larger by the time he returned. Indeed, at this time he wrote, "I felt as if something mystical was taking place between the all-knowing staff and their mechanical helpers…. Photographically I hope to capture and compare the harsh reality of man's finiteness with the mystical aura that surrounds the medical team and their sophisticated technology" (Payne c1970-72). In a later correspondence with Allan Porter of Camera magazine, Payne added to this basic sentiment, "From the very first I had a mysterious, mystical feeling about the machinery that was used in treating patients. And later I felt that the hospital staff was an extension of the machines" (Payne undated) PhiN 52/2010: 54 This began the move away from the lionization of the hero-surgeon to what Payne referred to, obliquely, as "the patient in relation to the hospital staff and the instruments" (Payne c1970-72). Outtakes from this phase not included in the final cut of The Patient as Object reveal he was beginning to see the isolating effects of machine-medicine on the patient, and a fabulous confusion of man and machine. In this sense, the images ask some of the same aesthetic questions asked (and provisionally answered) by the Futurists; and indeed, Payne's witnessing of the death of the hero-surgeon draws on both the Futurist appreciation for the potential of machines and the creation of wild new forms, as well as a conservative humanist aesthetic. In the context of medical technology, these questions become, 'where do man's immune and central nervous systems end and mechanical life support begin?' and 'are machines a barrier between physician and patient, or a vital link? Or somehow both?' and 'must technological expedience reduce humanness? – and if so, what becomes of First Do No Harm?' In Untitled Outtake 1, a mysterious hand, which reaches in from four o'clock to adjust or steady the child's mouthpiece, belongs apparently to a nurse obscured by the bulk of the machine. This ominously disembodied hand is made even more sinister by an inky shadow cast on its lower half, as if it has been transformed in the machine's perimeter. The hand, the child and the machine are, in reality, three separate entities, but we are momentarily bewitched into seeing them as one continuous flesh-metal entity. It is worth noting the analogy between Payne's "mysterious, mystical feeling" and Julian Offrey de la Mettrie's famous fever dream vision on the battlefield of Freiburg (1744), in which he saw clearly "that thought is but a consequence of the organization of the machine, and that disturbance of the springs has considerable influence on the part of us that metaphysicians call the soul" (Bussey 1912: 6). Whereas Descartes and others "had supposed an essence superior to matter," La Mettrie saw "only mechanism." The overall aesthetic unity of The Patient as Object very much reflects La Mettrie's key philosophical question: is man nothing more than a biological machine made of organized matter, responsive and 'connectable' to other machines? Most everyone can agree that medical technology, such as the MRI, has improved the effectiveness and, in some cases, the overall experience of healthcare since the days of drilling holes in the patient's skull, yet it is a truism that this evolution has come with a price. Witness the incubator featured in Untitled Outtake 14 – this most large and threatening thing, we must take upon faith, is a medical device, not a torture chamber. It may even bring to mind the mysterious 'apparatus' of Kafka's "In the Penal Colony" with its 'Bed', 'Designer' and 'Harrow'. From the Plexiglas target, positioned before the child's mouthpiece, a monstrous web of spokes, straps and chrome bars stabilizes his tiny, phlegmatized body at the apex of the machine. Below it we see the child's knee in a whorl of bed sheets, in which we lose the rest of him. This, although understandably an outtake from the final cut, is the most complete of all the images, in its summing up of the distance technology has opened between patient and physician, and of Payne's mystical vision. PhiN 52/2010: 55 One may argue that these concerns are strictly aesthetic and therefore immaterial to any proper consideration of healthcare, but consider the scope of changes the physician-patient relationship must undergo when machines intermediate, or replace the physician altogether. Consider what is lost when a physician forfeits his influence on the emotional life of his patients. A machine cannot reassure the patient, for example, his illness is not a moral issue, or a mortal threat. Physical touch, moreover, is one aspect of medicine that has remained constant as a tool of comfort, instinctively applied since the days of pre-modern medicine; its popularity continues worldwide among traditional healers. Lewis Thomas considered touching and the placing of hands to be "the oldest and most effective act of doctors". He goes on:

Thomas considered the invention of the stethoscope (1816) as the beginning of a technology that has increasingly distanced physician and patient. Ever more physically and emotionally remote, today's physician treats more patients more efficiently than ever before with an arsenal of mechanical and electronic equipment. In some cases the physician needs note even be present for analysis or treatment. While neither Lewis Thomas nor anyone else would argue that human hands and ears are more capable of recognizing neurological or biochemical abnormalities that computer diagnostics, something, as Thomas put it, "uniquely subtle" has been lost in the age of machine medicine. A marked progress in medical technology is evident even in the fourteen years between the completion of The Gross Clinic in 1875 and The Agnew Clinic in 1889, and this can be seen in a close examination of the paintings' details. Compare the degrees to which the operating team comes into direct contact with the patient, taking blood and offal onto their flesh and clothes in The Gross Clinic; and takes more sanitary care in The Agnew Clinic. Similarly, the surgical tools lying about in the open air of The Gross Clinic, are absent, perhaps kept in a sterile container, in The Agnew Clinic. This change is thanks to developments in bacteriological thinking during this period. Note also the change in the application of anesthesia from ether cloth (in the hands of a surgeon) in The Gross Clinic to ether cone (directly over the mouth of the patient) in The Agnew Clinic. Elizabeth Johns, in her 1983 study of Eakins, notes the rapid progress of medicine in those years and beyond: "Soon progress that amazed Agnew had been surpassed and even the clinic faded into history." (Johns 1983: 79). PhiN 52/2010: 56 At the forefront of the painting is Dr. Samuel Gross himself. Although surrounded by a team of assistants, by students and other observers, he stands alone, illuminated with a bloody scalpel. And although his eyes are partially obscured by shadow, his expression reflects "the old values – rationality, discipline and morality" (Johns 1983: 46). The Gross Clinic is a tribute both to Dr. Gross' international reputation as a surgeon, teacher and writer, and to a man with a "deep interest in his cases" (Gross 1887: xxvii) – the sort of man who would conclude his commencement speech with the words, "Whatever of life, and of health, and of strength remains to me, I hereby, in the presence of Almighty God and of this large assemblage, dedicate to the cause of my Alma Mater, to the interests of Medical Science, and to the good of my fellow creatures" (Gross 1887: xxvii).5 Although in the age of Dr. Gross and Dr. Agnew the mortality risk was far greater, as was the potential for pain, Eakins tames us with a sense of moral responsibility on Dr. Gross' part, while in the mechanical-electronic age of Mitchell Payne, this moral responsibility has been shifted, for the greater part, to a machine incapable of addressing it.

Among our very first impressions of The Patient as Object and its outtakes should be a sense of isolation, physical and emotional, of the physician and the patient. In contrast to The Gross Clinic, in which physicians, assistants and even an audience, surround the patient the man on the gurney in Untitled 10 is completely alone. He is as pallid as a corpse, yet he looks too uncomfortable to be dead. His being is as deflated as his body is bloated, and his life has dwindled so low he nearly escapes our compassion. Who are these nurses in the background? Though their backs are turned against him, we must be fair in not presuming any disinterest, reluctance or unfamiliarity. But we can be certain of a lack of focus in contrast with the curious and dedicated natures of the assistants in The Gross Clinic, who crowd busily around the operation. In Payne's world, the physicians have come to resemble the patients in their emotional removal from the situation. Note, for example, Untitled Outtake 2, in which three caregivers stand watching as a barrel-chested, cadaverous man undergoes a brain-scan – indeed, a gun to his head. The foreground is dark and gray in contrast to the warm light inside the observation booth. Although the physical distance between them and the patient is only a few feet, it seems immense. PhiN 52/2010: 57 If physicians no longer retain the posture and energy of the heroic Dr. Gross and his team, who or what have they become? Payne was well aware of this question when he wrote, "I was beginning to feel that the underlying character of the hospital was one of cold, impersonal efficiency" (Payne c1970-72). Payne asked one of the physicians on the team he photographed about the physician's emotional relationship with the patient and learned he "purposefully maintains a businesslike approach to his patients in order to maintain his sanity…. [A doctor] is there to fix the patient's physical condition and is not concerned with the patient's emotional needs" (Payne c1970-72). What a distance we have traveled, indeed, from Eakins' hero-surgeon, Dr. Gross, whose former patients "testified most feelingly that the lapse of nearly a quarter of a century had not dimmed their recollection of [Dr. Gross'] never failing kindness to them in the days that were dead and gone." (Gross 1887: xix). The separation of physical and emotional health in patients is still a divided issue among physicians thanks, by some opinion, to Cartesian thinking. On this subject the physician Francis W. Peabody noted famously in a lecture to Harvard Medical School that Disease in man is never exactly the same as disease in an experimental animal, for in man the disease at once affects and is affected by what we call the emotional life. Thus, the physician who attempts to take care of a patient while he neglects this factor is as unscientific as the investigator who neglects to control all the conditions that may affect his experiment (Peabody 1927: 882).6 But even if machines have not distanced physician and patient but rather established a more solid link between them, as one may argue, they have done so by allowing more vital data to be transmitted, in both directions. As a result, fewer physicians can now see a greater number of patients and more lives are saved than ever before. Yet a physician now is permitted, and perhaps encouraged, to see his patient as an EKG line, slowly pulsing, or as an X-ray pattern, a frozen two-dimensional instant. In Untitled 7, the patient under examination, Payne notes, "could easily be removed from the situation and replaced by a chart…." (Payne c1970-71). All this is coincidental, for it can hardly be argued that all nineteenth century surgeons were as heroic as Dr. Gross and all late twentieth century surgeons are as emotionally absent as those in The Patient as Object. Moreover, machines have not created autonomous, impersonal physicians; coldness and impersonality have always been a part of professional surgery. The famous Daguerreotype Early Operation under Ether, Massachusetts Hospital, attributed to Josiah Hawes and Albert Southworth (c. 1850, predating The Gross Clinic by at least twenty-five years) depicts a group of gothic-looking physicians gathered for a demonstration of ether anesthesia. Whereas Eugene Richards' 1980s work The Knife and Gun Club depicts emotionally spent Denver General ER surgeons who "go to sleep remembering what it was like when I was last there – the smells, the noises the wild eyes, the blood…." (Richards 1989).7 So it is aesthetics informed by history that allows us to see and feel what Thomas Eakins and Mitchell Payne, themselves, experienced, and what they had (and failed to have) in common. PhiN 52/2010: 58

Though Payne's vision of the project did not explicitly disregard history, he thought and wrote about the project in mainly aesthetic terms. He summed up his approach as such: "My primary concern is making images that succinctly express the essence of my feelings about a particular situation of thing; a concern with aesthetic imagery" (Payne c1970-71). That is to say, he was trying to deny or minimize the political dimensions of his work. Each of Payne's final-cut images and outtakes is composed of middle ground and background only, for immediacy and drama. From the foundation of either a sterile tile-grid wall or deep black space emerges the object of empathy, or perhaps an obstruction implying an object of empathy behind it. Most often he resists any sort of center, preferring to make our eyes scatter and search each corner for something to hold onto, just as he searched everywhere for humanness. Payne's eye was very sensitive to geometry, in this series and his others. Tight angles and straight lines serve both to vault the mood and to support a sense of order and efficiency not so much emphasized in Eakins' paintings. However, Payne resists the easy opportunity to make the machines look more monstrous and ugly than they really are; instead he finds a utilitarian, almost Bauhaus beauty in them. Lights, tanks, gurneys, incubators, hoses, scanners, and other more occult devices emerge from the foundation. Stainless steel and rubber wrap behind, over and beneath the hospital room like veins and arteries. More familiar objects like masking tape and latex gloves float on the surface to remind us we are still on earth. The Patient as Object does not so much lead us to a dark place as abandon us with an uncertain future. The Gross Clinic, for all its tension and offal, does neither. The magnificent Dr. Gross, as Eakins depicts him, stands watching over his operation, keeping up both our spirits and the patient's. He and Dr. Agnew are the answers to our every mortal fear. PhiN 52/2010: 59

Payne's success in portraying what he termed "something mystical" involved a technique quite unlike the Futurists, or like Minor White or Kandinsky – all of whom developed unique ways to visualize the unvisualizable. Indeed, The Patient as Object has very little in common with the various spiritual or metaphysical art movements, although these styles may well have appealed to Payne. Most often his lack of foreground, choices of angle and high contrast are enough to isolate the otherworldly and ritualistic qualities of surgery. The issue of contrast is not limited to light and shade, however. Much like Wynn Bullock in his nature series, Payne juxtaposes opposites: weakness and strength, sepsis and asepsis, innocence and wisdom, the vast and the small, or beauty and ugliness to amplify the qualities of each, and in doing so achieves, as did Wynn Bullock with his similar technique, "another level of reality" (Davis 2001).8 Though the work of Mitchell Payne and Thomas Eakins shares specific humanist aesthetics and a need to immortalize what they admire, their individual experiences in the operating chambers, and their denouements, diverge most sharply. Lest this be considered a flaw, let us remember that irresolution, or perhaps insolubility, was an aspect of Mitchell Payne's overall worldview, and modus operandi as a photographer. For example, Strippers, a series also from 1970, features a New York sex-worker explaining how normal her depraved life is. Even the more light-hearted compilation of found photographs, American Snapshots (Scrimshaw Press, 1977, co-edited with Ken Graves) is a project designed, much like Mandel and Sultan's Evidence, published only months before, to baffle and ignite the imagination. Payne may have absorbed this quality from W. Eugene Smith, whom he cites in his thesis statements9 , and with whom he also shares the ability to shoot from deep inside a subject and remain invisible. Or perhaps this quality came somewhat in spite of himself, since it seems he found in The Patient as Object exactly what he set out not to find. Payne's longtime friend, photographer Ken Graves said of him, "Mitchell saw the world as fractured and without resolve, like so many of us did after Robert Frank" (Graves 2001). PhiN 52/2010: 60 Where is the heroic Dr. Gross in The Patient as Object? Mitchell Payne, as we have seen, very much wanted this to be his brother and his brother's colleagues, but the photographs tell us otherwise. But on this matter Payne wrote nothing explicit in his notes. So without a hero-surgeon or any other self-contained resolution, The Patient as Object sinks into irresolution. While The Gross Clinic and The Agnew Clinic are unambiguous in their dedication to the heroic surgeon of the nineteenth century, The Patient as Object is, in the same sense, a stunning failure to locate the myth a hundred years later. Thankfully, its author's perseverance has bequeathed to us something far more important than an updated adulation of heroic physicians and hope in the hospital room. The machines, ultimately, have not helped surgeons maintain their heroic identity, or become more superhuman; they have reduced the hero-surgeons to mechanics.

Mitchell Payne had only begun a body of work poised to ask challenging social questions when he was murdered on August 19th, 1977. Ultimately The Patient as Object will stand as his strongest work, and will remain as a bittersweet epilogue to Thomas Eakins' paean to Drs. Gross and Agnew – a vision of the real yet uncertain territory beyond the humble assurances of these two good doctors. PhiN 52/2010: 61 BibliographyBussey, G.C. (1912): Man a Machine, Chicago: Open Court Press. Davis, Keith F. (2001): Wynn Bullock: Realities and Metaphors, New York: Laurence Miller Galleries. Graves, Ken (2001): Personal Communication. Gross, Samuel W. & A Haller (1887): The Autobiography of Samuel D. Gross, M.D., two volumes, edited by Samuel W. Gross and A. Haller Gross, Philadelphia: George Barrie. Johns, Elizabeth (1983): Thomas Eakins: The Heroism of Modern Life, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Kirkpatrick, Sydney D. (2006): The Revenge of Thomas Eakins, New Haven: Yale University Press. Payne, Mitchell (c1970): Thesis statement, first draft (unpaginated, unpublished). Payne, Mitchell (c1970-71): Thesis statement, second draft (unpaginated, unpublished). Payne, Mitchell (c1970-72): Personal notes (unpaginated, unpublished). Payne, Mitchell (Undated [mid-1970s]): Correspondence with Allan Porter (unpaginated, unpublished). Peabody, Francis W., M.D. (1927): "The Care of the Patient". In: Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 88, March 19. Richards, Eugene (1989): The Knife and Gun Club, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. Thomas, Lewis (1983): The Youngest Science: Notes of a Medicine Watcher, New York: Viking Press. PhiN 52/2010: 62 Notes1 Payne actually mentions "my final thirty prints" in the second draft of his thesis statement, yet in his individual descriptions, he only refers to thirteen. Whether by "thirty" he meant "thirteen" or whether seventeen have gone missing is unknown at present 2 "Dr. Duke" is almost certainly a pseudonym for Nettleton Payne. Though Payne does not mention his brother in his early notes, or in his thesis statement for Neurosurgeons in Action for whatever reasons, in the thesis statement for The Patient as Object he does mention him, implying the connection. His reasons for this initial concealment are unknown. 3 Underlining is in original. 4 None of Payne's images from either Neurosurgeons in Action or The Patient as Object are, evidently, titled. All titles in this article are provisional. 5 This speech was given upon Dr. Gross' commencing as professor of surgery at Philadelphia's Jefferson Medical College. 6 Although Dr. Peabody's belief regarding the emotions of animals is now outdated, it does not subtract from his overall point. 7 Quote is from unpaginated prologue. 8 Quote is from unpaginated introduction. 9

Payne writes in the second draft of his thesis statement, "Particular attention will be paid to the work of W. Eugene Smith and Henri Cartier-Bresson…."

Acknowledgments

Linda M. Montano

|